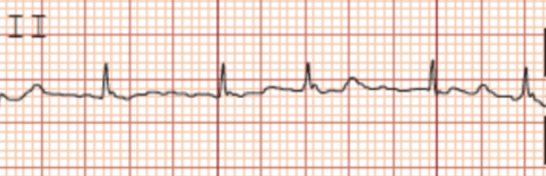

Rapid, irregular contractions of the atria (quivering or “fibrillating”) with variable ventricular rate. The rhythm itself is benign, but it is prone to causing a reduced left-ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), which can lead to a reduced cardiac output at elevated heart rates. Along with this, the incongruent contractions of the atrial walls may lead to hemostasis within these chambers, allowing for formation of an intracardiac thrombus (most often within the left atrial appendage).

Notice how there are no p-waves, but there are “fibrillatory” waves between QRS complexes. The rhythm is also irregularly-irregular.

4 Categories

- Paroxysmal: Occasional episodes that terminate spontaneously (or therapeutically) in <7 days

- Persistent: Episodes that last >7 days

- Long-term persistent: Episodes that last >12 months

- Permanent: When atrial fibrillation is accepted by both patient and provider and no further attempts at conversion to sinus rhythm will be made

Causes

- Heart Failure

- Valvular heart disease

- Acute Coronary Syndrome

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- Hyperthyroidism

- Pain

- Infection

- Dehydration

- Electrolyte derangements (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia)

- Initial workup should involve a BMP, TSH, and echocardiogram. Depending on patient’s presenting clinical picture, clinicians may want to consider ruling out acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or infection. Most patients should be considered for a polysomnogram.

Management

- First step is always A, B, Cs (Airway, breathing, circulation)

- If hemodynamically unstable, synchronized cardioversion is necessary

- If hemodynamically stable with HR > 100 bpm (rapid ventricular response), goal is to keep heart rate < 110 bpm (1)

- Achievable through use of PO or IV Metoprolol, or commonly a titratable continuous IV diltiazem infusion may be used. Typically, calcium channel blockers should be avoided if the patient has a reduced ejection fraction. Of course, the blood pressure needs to be able to tolerate these anti-hypertensive medications, though the blood pressure may actually increase with the use of AV-node blocking agents as the slowed heart rate allows for a larger end-diastolic volume (EDV) and, therefore, an increase in cardiac output

- Acute (new-onset and with certainty that it has initiated in the past <48 hours)

- Cardioversion

- Electrically (synchronized cardioversion)

- Pharmacologically (Flecainide, amiodarone, sotalol, dofetilide, etc.)

- Anticoagulate for at least 3-4 weeks after

- Cardioversion

- Chronic (rhythm has persisted over 48 hours or it is unclear how long the episode has lasted)

- Anticoagulate for 3-4 weeks or perform TEE to assess for thrombus in left atrial appendage prior to cardioversion

- Cardiovert (either electrically or pharmacologically as above)

- Other options include AV node ablation with pacemaker insertion or atrial fibrillation ablation (usually at the pulmonary veins, where atrial fibrillation most commonly originates from)

- Anticoagulate for 3-4 more weeks (or indefinitely based on CHA2DS2VASc score)

- CHF = 1 point

- Hypertension = 1 point

- Age; 65-74 years old = 1 point; 75+ years old= 2 points

- Diabetes = 1 point

- Stroke history = 2 points

- Vascular disease = 1 point

- Sex Category (female) = 1 point

- 2+ points is an indication for long-term anticoagulation (though this risk should be weighed against the risk of bleeding, calculated with a HAS-BLED score)

- Alternative to anticoagulation may include placement of left atrial appendage closure device for patients with bleeding issues

- Long-term management of atrial fibrillation that is refractory to conversion to normal sinus rhythm

- Rate-Control (Beta Blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin) if necessary, though occasionally patients are intrinsically rate-controlled

- Anticoagulation

- Using CHA2DS2VASc score as above

- Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation: DOACs may be used (apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, etc.). Low-molecular weight heparin or warfarin may also be used

- Valvular Atrial Fibrillation: Traditionally, warfarin was preferred over DOACs, but there is now growing evidence for DOAC use. Several specific scenarios may warrant additional consideration (i.e. mechanical valves or patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis should be anticoagulated with warfarin and not DOACs) (3), (4), (5)

References

- Gelder, I. C., Groenveld, H. F., Crijns, H. J., Tuininga, Y. S., Tijssen, J. G., Alings, A. M., . . . Berg, M. P. (2010). Lenient versus Strict Rate Control in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(15), 1363-1373. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1001337

- A Comparison of Rate Control and Rhythm Control in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. (2002). New England Journal of Medicine, 347(23), 1825-1833. doi:10.1056/nejmoa021328

- Eikelboom, J. W., Connolly, S. J., Brueckmann, M., Granger, C. B., Kappetein, A. P., Mack, M. J., Blatchford, J., Devenny, K., Friedman, J., Guiver, K., Harper, R., Khder, Y., Lobmeyer, M. T., Maas, H., Voigt, J.-U., Simoons, M. L., & Van de Werf, F. (2013). Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(13), 1206–1214. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1300615

- Wang, T. Y., Svensson, L. G., Wen, J., Vekstein, A., Gerdisch, M., Rao, V. U., Moront, M., Johnston, D., Lopes, R. D., Chavez, A., Ruel, M., Blackstone, E. H., Becker, R. C., Thourani, V., Puskas, J., Al-Khalidi, H. R., Cable, D. G., Elefteriades, J. A., Pochettino, A., … Alexander, J. H. (2023). Apixaban or warfarin in patients with an on-X mechanical aortic valve. NEJM Evidence, 2(7). https://doi.org/10.1056/evidoa2300067

- Kotit, S. (2023). Invictus: Vitamin K antagonists remain the standard of care for rheumatic heart disease-associated atrial fibrillation. Global Cardiology Science and Practice, 2023(1). https://doi.org/10.21542/gcsp.2023.6